To start it was mostly a crazy notion sparked by the improper desires of two proper white women craving adventure and freedom.

To start it was mostly a crazy notion sparked by the improper desires of two proper white women craving adventure and freedom.A Mr. Kelsey was staying with Cousin Annie at the time we were there. We learned he was Special Agent for all Indians in California, and we told him we should like to see what a really rough country was like. Mr. Kelsey looked at our pleated skirts, seven yards around the bottom, and down to within an inch of the floor, and his eye hardened.

“Shall I send you to the roughest field in the United States?” he asked.

I think he expected us to refuse. But of course we did not refuse. It was the chance we had been hoping for.

The request was approved, and bets happily placed against the odds of the women’s survival. But survive they did, and spectacularly. As if the river crossings and bridge breakings and floods and landslides and panthers and rattlers and lice aren’t enough, there’s the lethal frontier combo of guns and liquor.

I would love to be a movie producer and casting director with the resources to put this story on the big screen.

It is the true account of Mary Arnold and Mabel Reed from New Jersey, childhood friends and life-long partners, who in 1908 at the age of 32 applied to be “field matrons” for the United States Indian Service of the Department of the Interior. Understandably they were calculating as hell about their approach in a region still called the wild west.

It’s bad enough for us to be women (Mabel said to Mary). No one thinks much of women in this country, and no one likes them, and missionaries are even worse. We simply can’t be missionaries. And government agents are worst of all. No wonder people won’t look at us or speak to us. But schoolmarms are safe. And everybody knows about them. They may not particularly like schoolmarms but at least they think they are harmless. As long as we stay in this country, we are going to be schoolmarms, and if the Lord didn’t cut us out to be schoolmarms it is just too bad for us, for that is what we are going to be.

One expects schoolmarms to be resourceful, but two things made Mary and Mabel exceptional: incredible physical stamina and utterly open minds.

The journey north from San Francisco to “the Rivers,” the Klamath and the Salmon, required days on horseback in the rain. Given an available mail rider, the women followed him. Between mail routes they were on their own.

It was not one mountain along which the trail led but a jumble of mountains. We would slide down a sharp incline, cross a creek, and struggle up the mountain on the other side. Then we would come out on another narrow cut, with the steep cliff above and the sheer drop below, and try to make a little better time. At first I was too much alarmed by the character of the trail to notice anything else . . . then I began to notice a large variety of aches and pains. . .

They were assigned to the Karok tribe under the auspices of, I think, the Episcopal church, which meant conducting church services, but there's no indication that they attempted to convert anyone, and services were mostly singing. Hymns and Christmas were popular, with an emphasis on Indian interpretations of songs and traditions, including drumming and dancing.

School proved popular as well, and children and adults attended.

The number of Indian men who came to school doubled, then trebled. A wonderful time was had by all, with one exception. While the class shouted with laughter and yelled and stamped as they competed to find answers, the unfortunate instructor (Mary wrote about herself), who has always been extremely poor at arithmetic, strove in mental anguish to arrive at the correct amount before anyone else . . . but heaven help me.

She could not keep up with her adult male students in math, and most were taking their introductory course. One of them, called Bernard, was in short order capable of taking over the class. “Bernard learned to multiply in one lesson. He cleaned up long division in another . . . and I rode back home in a state of collapse.”

When advised by an Indian woman called Essie that they needed to belong to a family, Mary and Mabel concerned themselves with adapting to suit hers, Essie being a tribal matriarch with three husbands whose household dominated the first community in which the women settled. These Indian communities, called rancherias, were allowed on government land, mostly remote parcels supposedly unavailable for purchase or development by whites but beholden to the Department of the Interior.

The boom-and-bust towns of the Gold Rush had introduced the Karok to white ways; white clothing, names and money were widely in use, and many Karok spoke at least some English. The official objective of the assignment was to help “civilize” the Indians, but the women’s personal objective was mutual understanding. Clearly ahead of their time, they hoped the best of both worlds would eventually merge, Indian and white. Impossible, given the inequities, but Mary and Mabel would do their best to challenge them, and started by not taking themselves too seriously.

The Indians do not take us at all seriously. We are just friends of theirs. But to Mr. Hunter and Mr. Wilder, white men and foresters, we are not only white women, we are ladies, the kind who have Sunday School and never say a bad word . . .We do the best we can and listen to what they say and try to act as though we never, never did such unladylike things as ride trails and cross rivers, but it isn’t always easy for the foresters, and here they were on a dark and possibly stormy night, come for a quiet evening with two perfect ladies, and not a chair in sight.

I wish the account offered more historical context and some follow-up, and am giving four stars because somebody, during a reissue, should have filled in. But even lacking that, the detailing of habits, quirks, friendships, and growls provides a fascinating look at a rare cross-cultural communion. A growl being an argument.

Occasionally a growl escalated into a feud. In one such case, the women were called upon to help a Karok family keep their home, a little ranch house they had built on a lovely spread they’d been farming for years. A white man decided he wanted it, and the U.S. government, of all things, let the white man have it. So long, Indian family, end of story, and now shut the hell up, Mary and Mabel. Except that it wasn’t really the end, it was really only the beginning. It would happen again and again: Indians being booted off government land as white sprawl consumed more and more of California. The women petitioned to extend their stay with the Karok but were denied.

There are a few other GR reviews of this book out there, and I’m surprised that they aren’t more enthusiastic. I couldn’t put the book down, and would love to get into the Mary and Mabel special collections at Swarthmore and Radcliffe. I’d also like to visit the Karok tribal center and find out what their historical collections have to say. Then I'd like to make a movie.

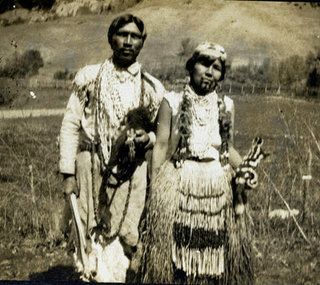

Haven't found a pic of Mary and Mabel, but this is a good one of Essie and husband Les.